Endorsing Rights, Increasing Visibility: Gay and Lesbian Activism after the Democratic Transition

The fall of communism in Central and Southeastern Europe brought a fundamental restructuring of the political institutions in these regions, accompanied by a reconstitution of their civil societies. These changes had a tremendous effect on the further development of political activism of LGBT+ persons in each of the countries. Suddenly, the realities that LGBT+ persons faced, became in some cases drastically different, the two extremes being Germany and the former Yugoslavia. For many East German gays and lesbians, the reunification of Germany meant access to an even broader, well-developed and “institutionalized” LGBT+ culture. On the other side the war in Yugoslavia significantly reduced the space for the development of the emerging LGBT+ activism from the 1980s, setting it on the margins of the devastating ethnic wars, where the only identity politics that was given weight in the public was the one of nationalism and ethnic cleansing.

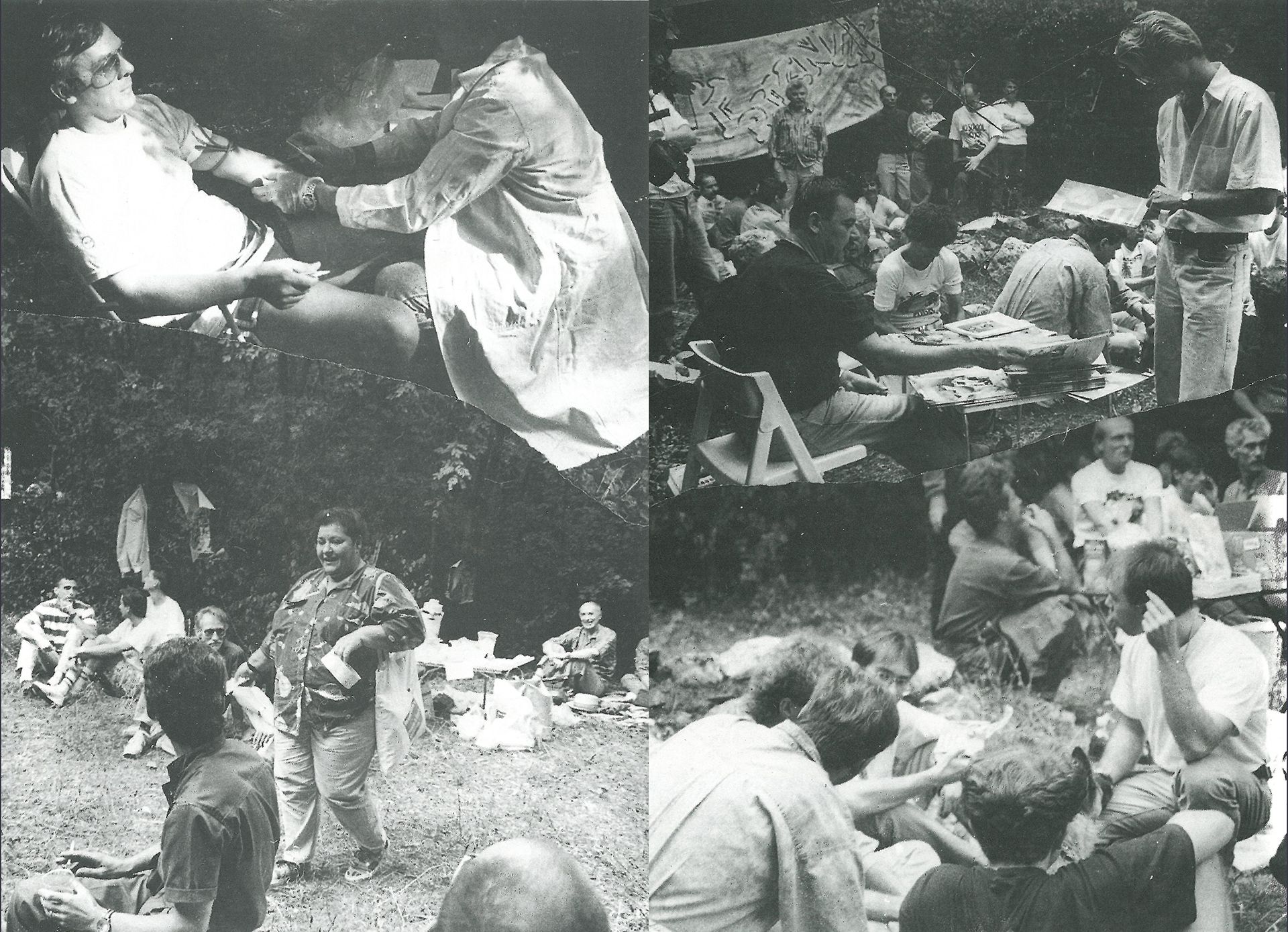

…I would remember an essay in off our backs, from many years ago, back in the 1980s, where one lesbian writer from the USA who went for a year to work in Nicaragua came back and said, ‘No I could not talk about my lesbianism in Nicaragua, there is a war going on there, they have some other priorities’. I replayed this sentence in my mind a thousand times; do I agree or not, and what would I say now? Every time I thought ‘No it isn’t right’, I would move on and think maybe it was; people first of all need to be able to live. If I would start with ‘Yes, it’s right’, I would then wonder if it was interiorized homophobia. Then one night in 1995 we had a Labris action in the old part of Belgrade, Dorcol, a few blocks away from my flat. Three men stopped four of us while we were writing lesbian graffiti. They came and attacked us precisely because we were lesbians. Two of them were at the back with hockey sticks and one of them stood in front of me. He watched me, I watched him, and I thought ‘This is a face that demands war. This is a face that kills. This is a face that has been produced as such in recent years, there are weapons of hatred behind him.’ I had never seen him before. He pushed me to the wall, broke my glasses and shouted, ‘You dirty lesbian, I can throw you in this door and kill you – no one would know. Clear off!’ When I asked him who he was, he exclaimed, ‘Don’t you utter your dirty words. The mosque is the place for you.’ Lesbians were dirtying his straight male street, just as Muslims were dirtying his straight Serb street. Gay men were being harassed in their parks, Roma people were being spat upon, women were forever the first victims of their husbands.

It took me some days to recover. After that, it was evident that war implies hatred directed against every difference, against Muslims in Belgrade, then against Roma, Albanians, lesbians – once they were Jews and Communists. And that opposing war means coming out with the logic of supporting all social differences at once. One of the aims of war and pro-fascist ideology is not only separation of people of different nationalities, but the separation of people’s own identities as well. That is how they can control us better. They need to have only two sets to control: ‘Us’ and ‘Them’, to reduce the fullness of our social beings to one.”

article excerpt, exhibition print

Courtesy of Lepa Mlađenović

Photo of Lepa Mlađenović, feminist, lesbian and anti-war activist in SFR Yugoslavia and Serbia, 1994

photo, exhibition print

Courtesy of Lepa Mlađenović

Gay Pride march in Budapest, 1997

video

Háttér Archive and Library (courtesy of Douglas Conrad)

Bulgarian homosexuals take off the fig leaf of their secrecy, 1991

press clipping from the Bulgarian “Trud”, exhibition print

IHLIA, Amsterdam

“Homosexuals in Albania also have a society of their own”, 1994

press clipping from “Gazeta Shqiptarë”, exhibition print

IHLIA, Amsterdam

Cover of the first newsletter of the Romanian organization, ACCEPT, 1996

newsletter, exhibition print

ACCEPT, Bucharest

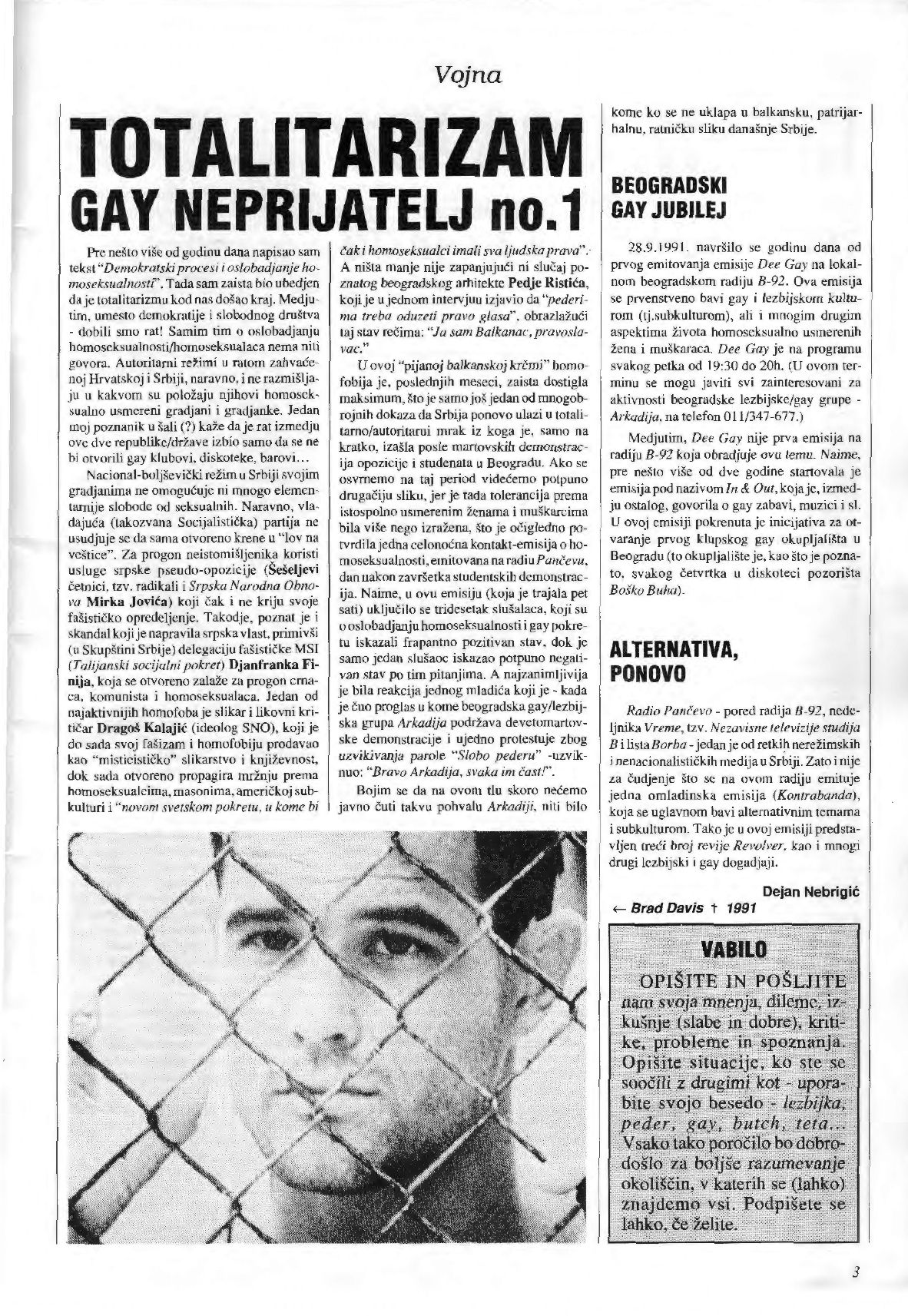

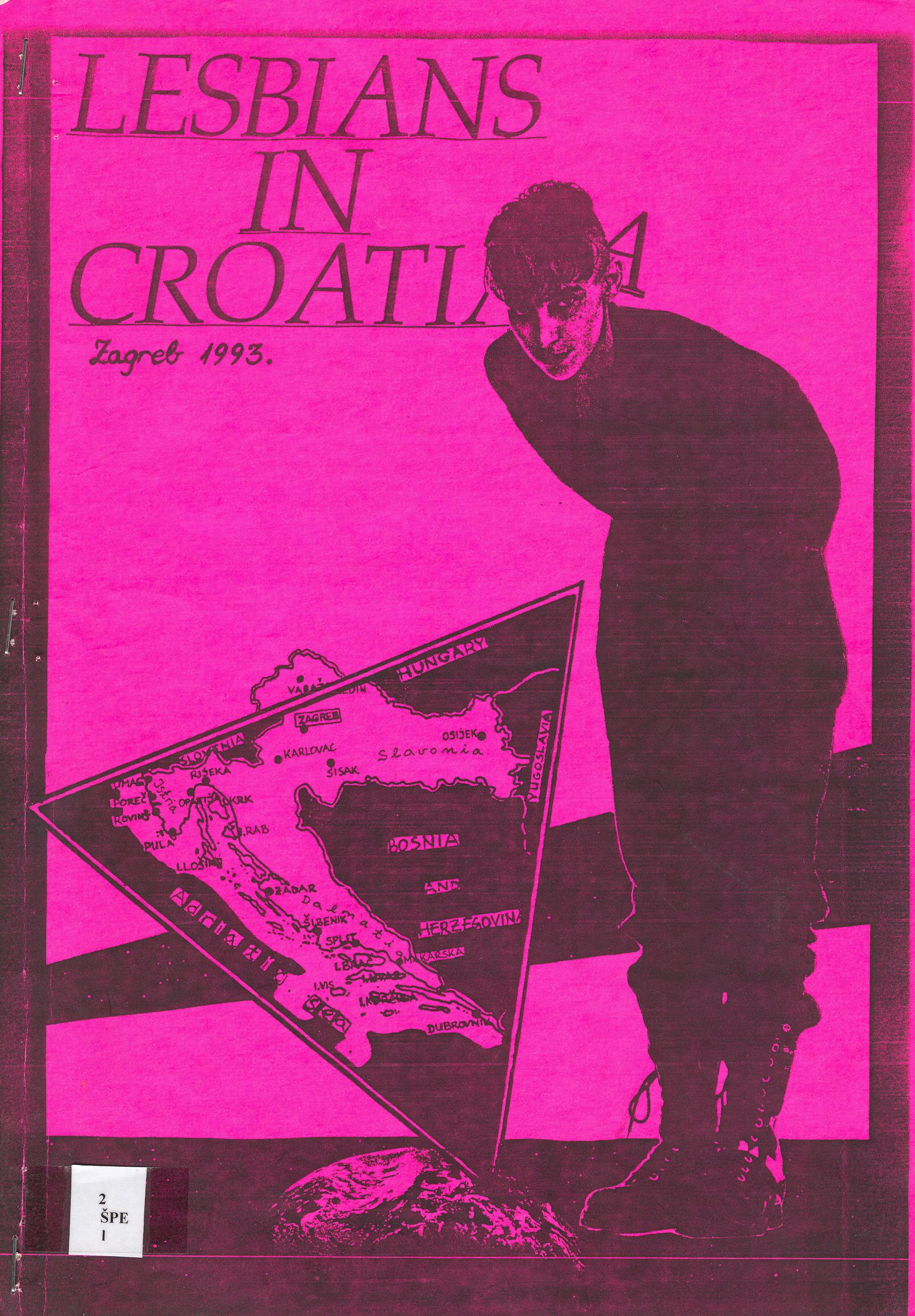

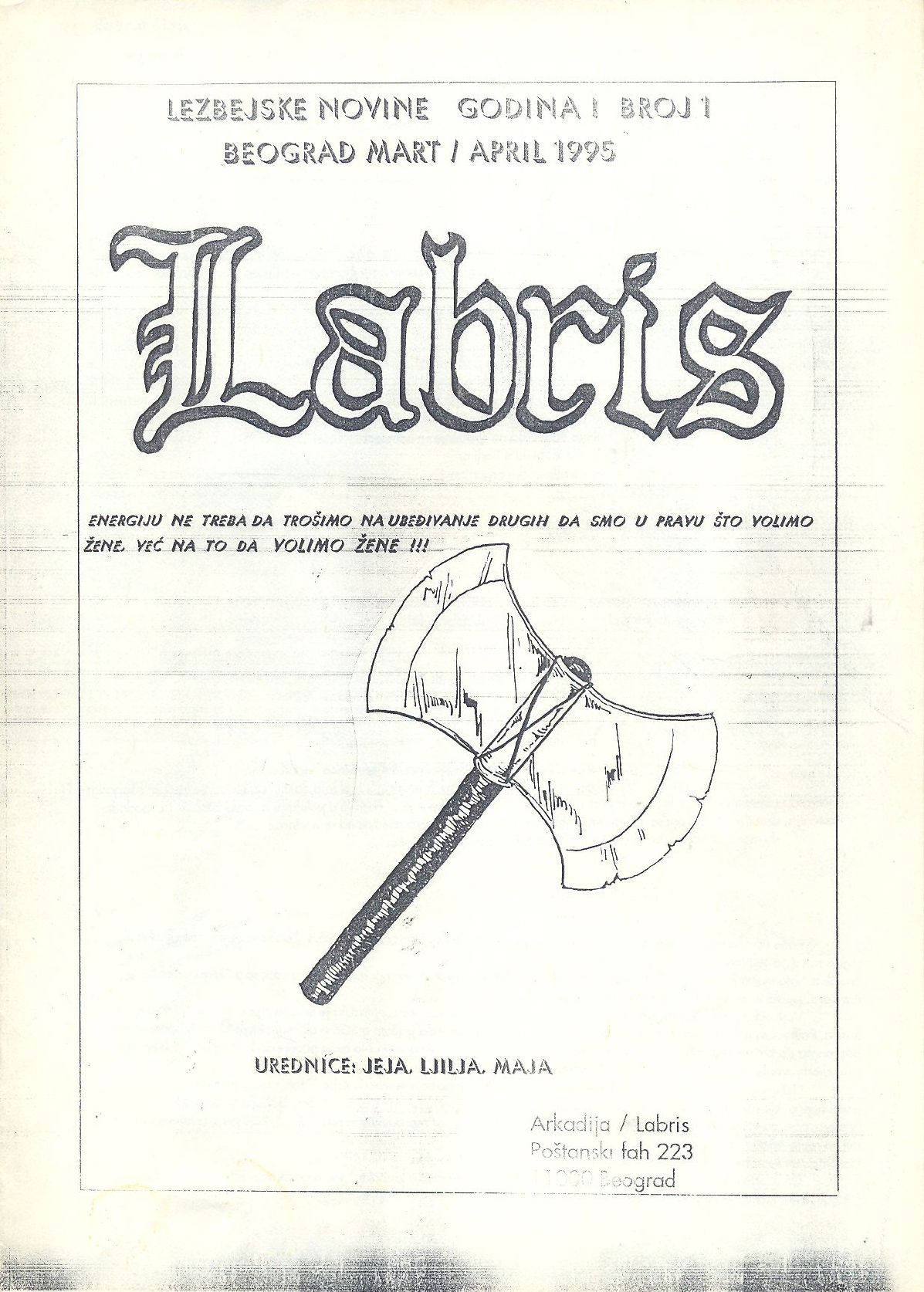

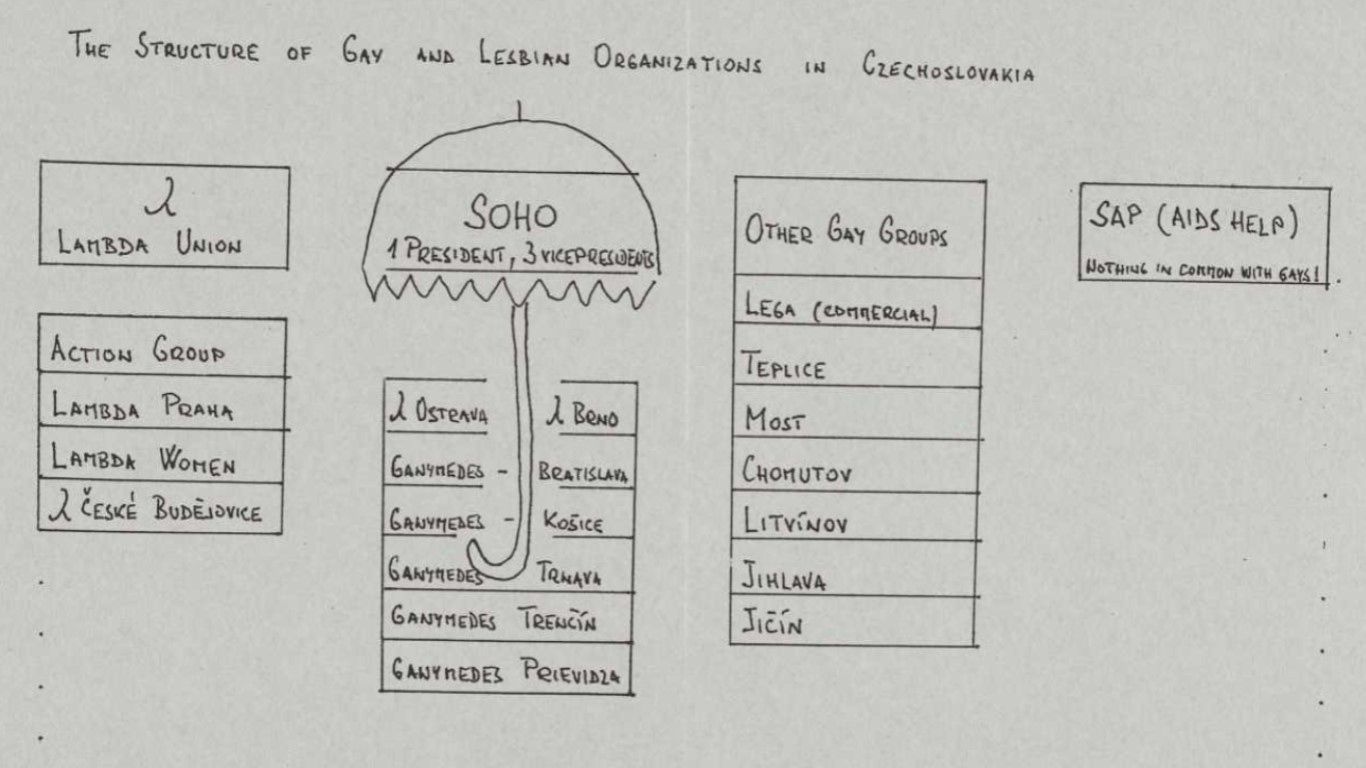

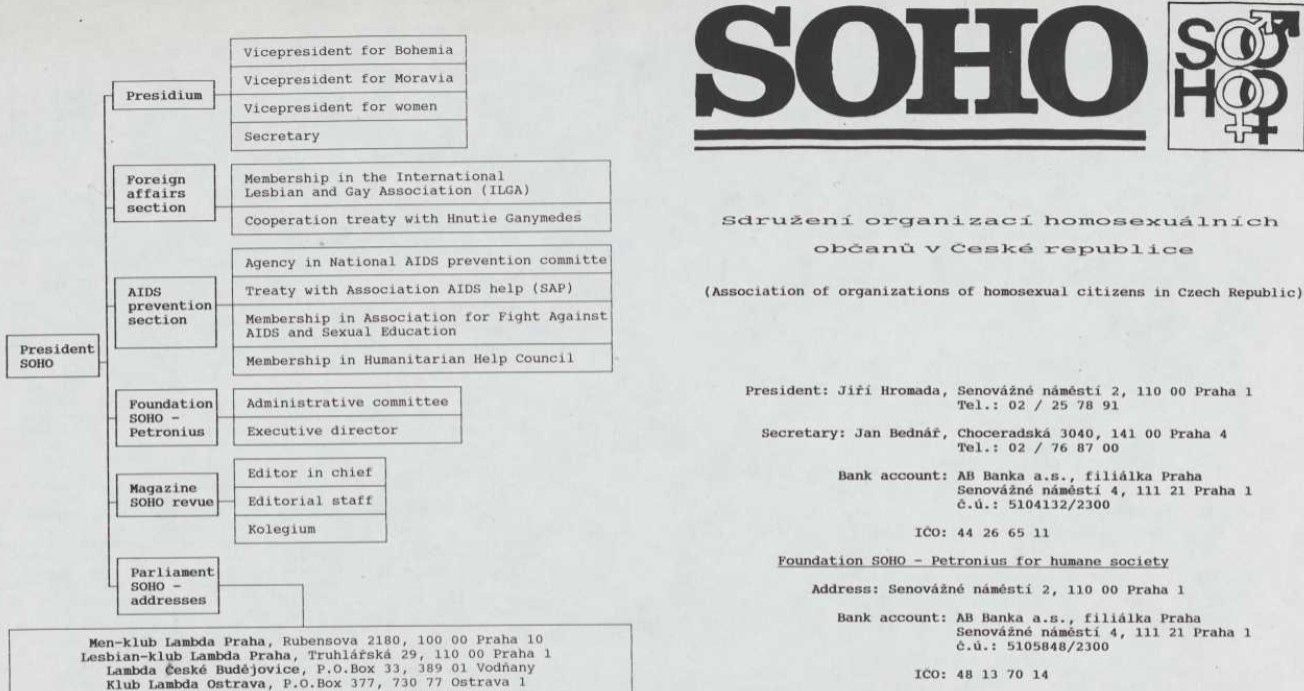

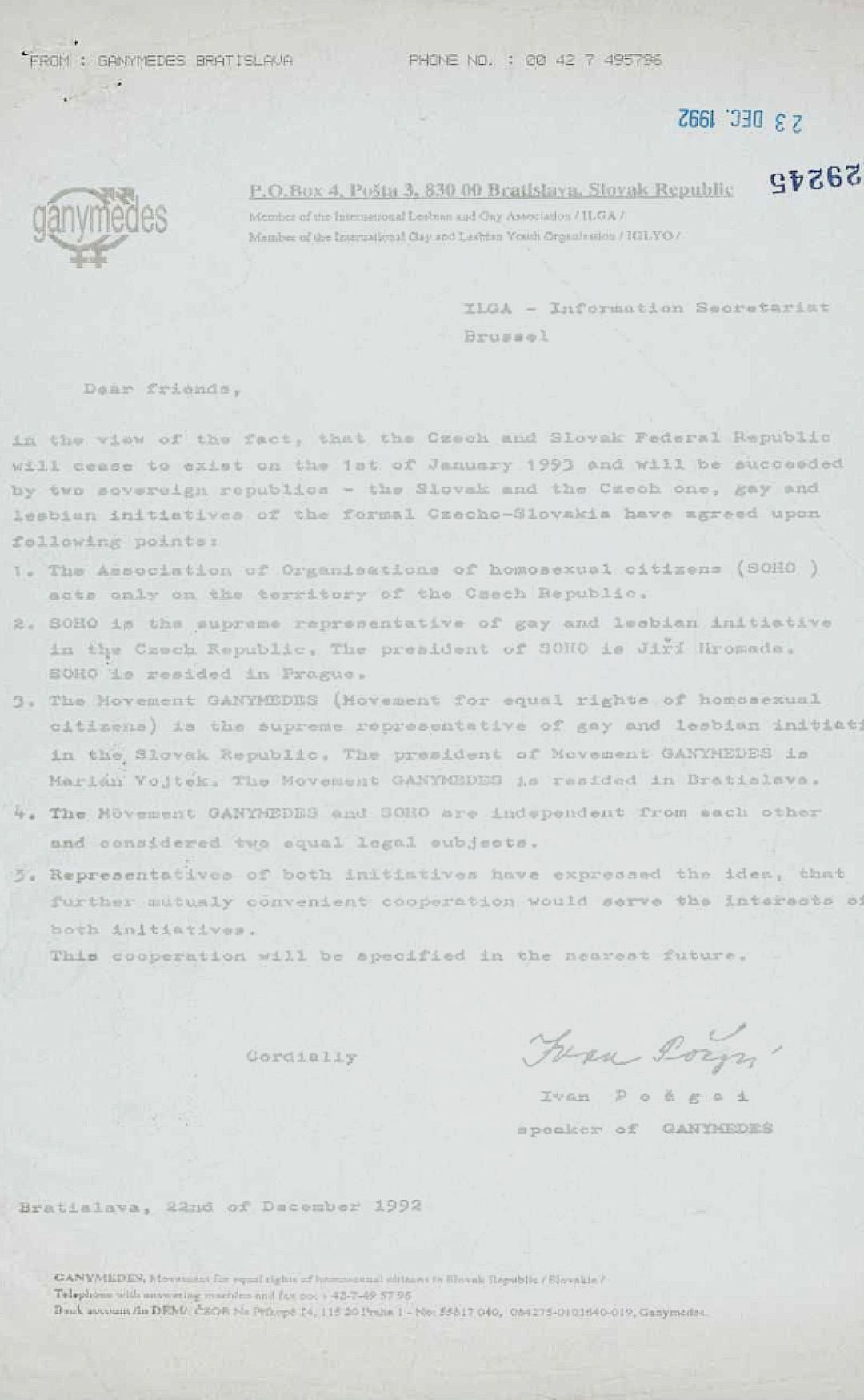

A common trend among the first registered LGBT+ organizations after the democratic transition was an almost general appropriation of the human rights perspective on the issue of sexual orientation and gender identity, as well as their integrationist perspective regarding the place and the role of gay and lesbian persons in the newly democratized societies. This is most clearly visible in the agendas of the Shoqata Gay Albania, Gemini in Bulgaria, ACCEPT in Romania, Arkadija and Labris in Serbia and the SOHO Association, initially in the Czechoslovakia. The reasons for taking the human rights perspective are multifold and complex, but should primarily be associated with the successes of the international human rights movement in these countries in the last days of the communist regimes. Moreover, the forums for transnational communication between LGBT+ organizations as well as international funds for sexual minorities were provided by international organizations with strong human rights orientation. The reasons for taking the integrationist perspective are also diverse, but mainly related to disillusionment with revolutionary, especially communist ideals. It was only at the end of the 1990s and the beginning of the 2000s that radical leftist LGBT+ collectives emerged in some of these countries.

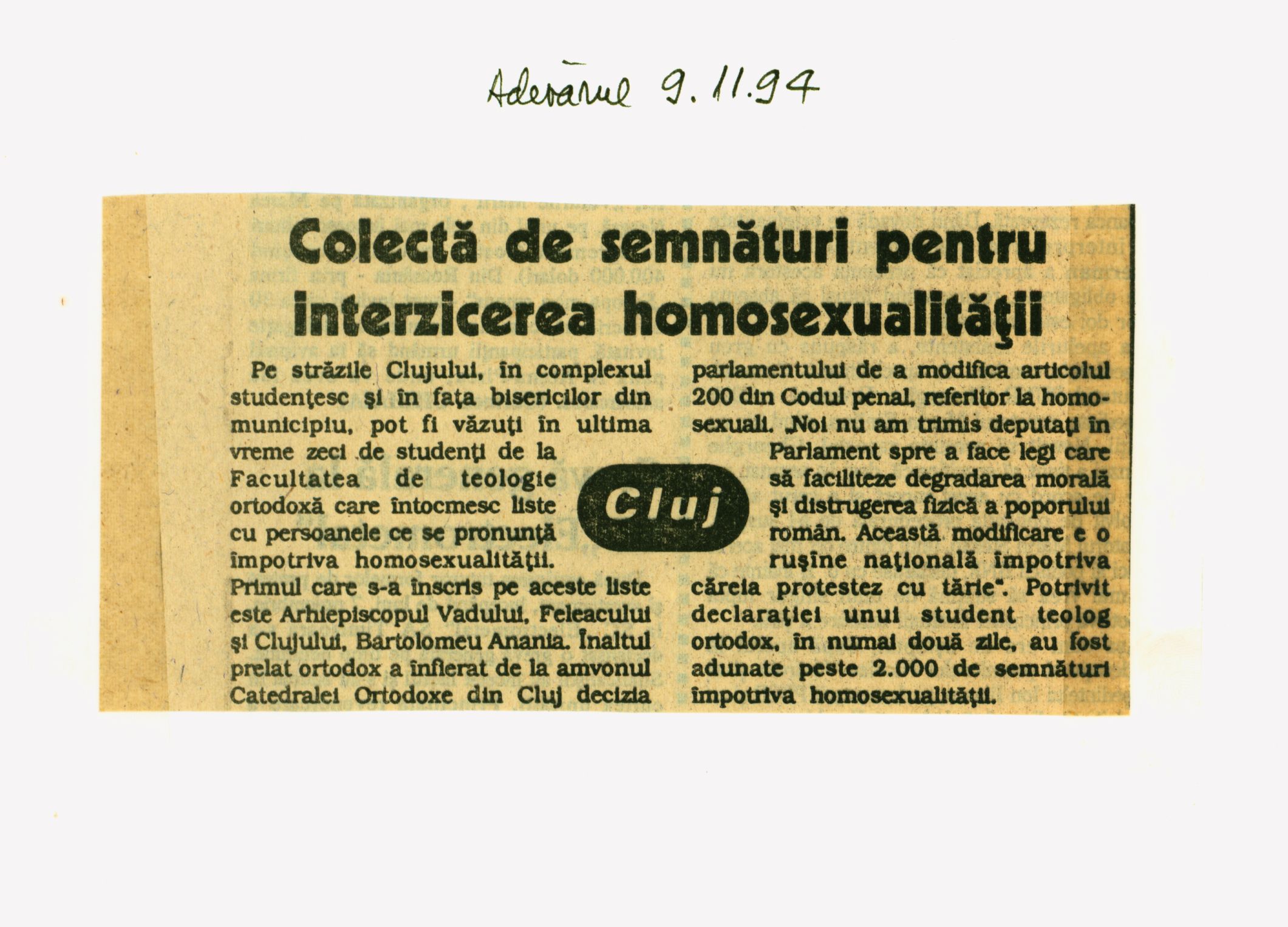

The increased public and media presence of the first gay and lesbian organization in the regions, was followed by a rise in homophobia among the general public and increased violence against activists and LGBT+ people by different groups, most of them nationalist, far-right and radical in nature. In Albania, a Nazi-group declared war on faggots immediately after the formation of the Shoqata Gay Albania; in Romania, aside from the constant homophobic statements and initiatives by the Orthodox Church, a massive anti-gay protest in 1998 opposed any change of the status-quo regarding Article 200; in Serbia a decade of state-sponsored homophobia culminated in 2001 with bloodshed during what was supposed to be the first Belgrade Pride.

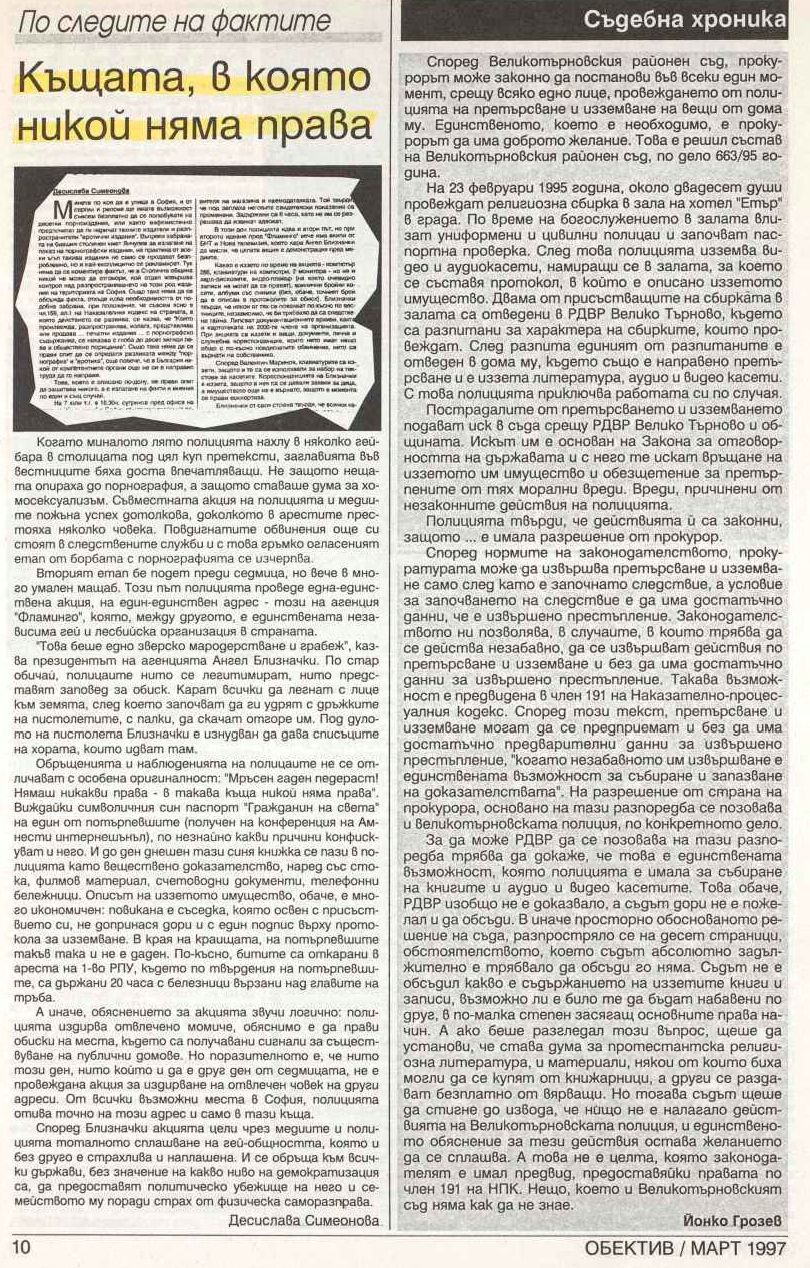

“The house where no one has rights”, article on the police intrusion in the premises of the contact agency and erotic shop Flamingo, 1997

press clipping from “Obektiv: Monthly Bulletin of the Bulgarian Helsinki Committee”, exhibition print,

IHLIA, Amsterdam

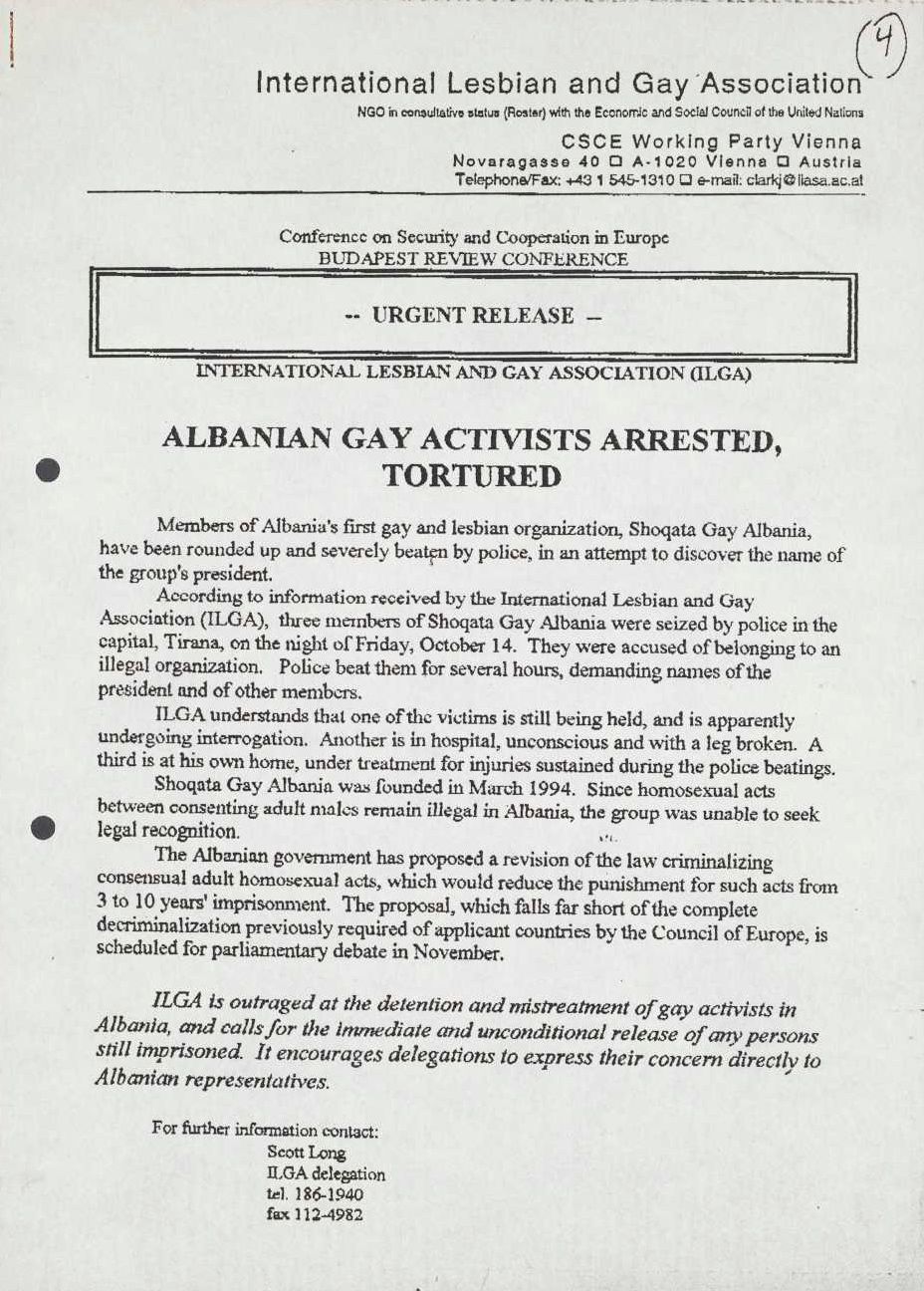

ILGA demands urgent release of Albanian Gay Activists, 1994

correspondence, exhibition print

IHLIA, Amsterdam

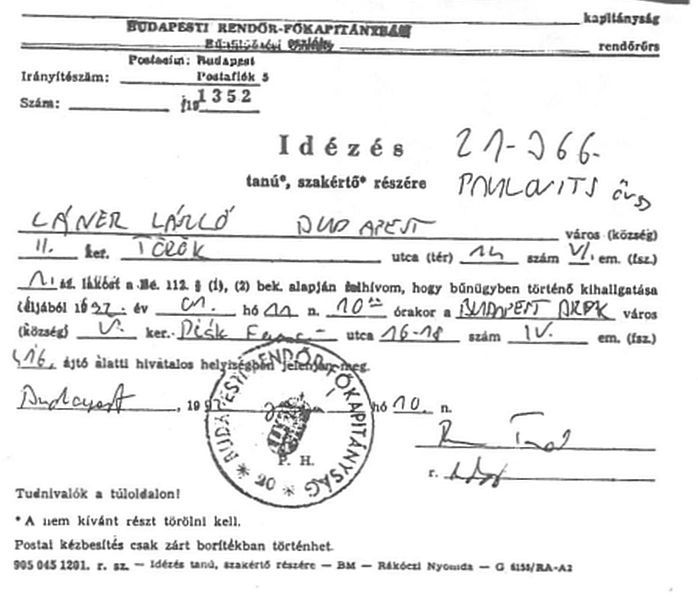

Police summons to “Mások” editors, 1991

summons, exhibition print

Háttér Archive and Library